Published in The Wire 27.04.2025

Instead of strengthening local bodies, the Waqf amendment has handed power to individuals who are far removed from local context.

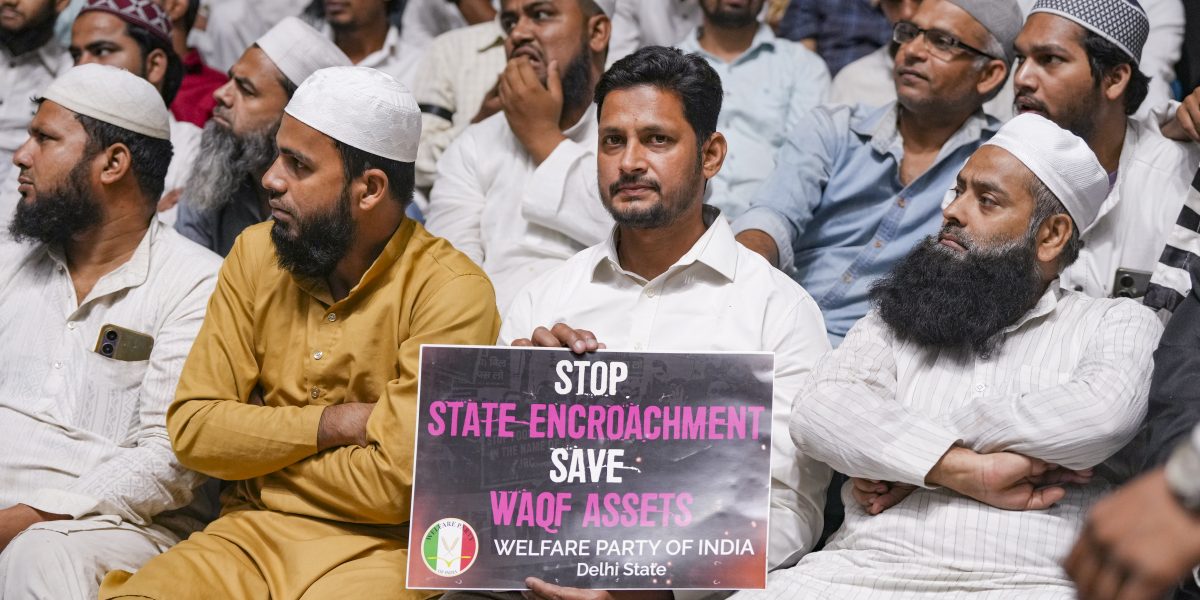

The Unified Waqf Management Empowerment Efficiency and Development Act, popularly known as The Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025, has drawn unprecedented attention following nation-wide protests and sporadic violence since it was passed.

The fear among the Muslim community primarily emanates from the notion that their autonomy over Waqf lands and buildings – on which mosques, schools, and charity organisations have been running for centuries – will be severely curtailed by the newly amended Act. They fear that new legal changes may even make it mandatory for them to take permission every time they take the dead bodies of their kin to a qabrastan (cemetery).

The Supreme Court has granted an adequate hearing over two consecutive days and pointed out a logical flaw in the amendment by asking whether Hindus would accept the imposition of Muslim members in the management of their temples by the government. The apex court also noted the Union government’s assurance that properties will not be denotified until the next date of hearing, scheduled for May 5.

The amended Act has amounts to an intrusion into the Muslims personal laws and is contrary to the constitutional principles enshrined in Article 25, 26 and 29. These articles categorically and unequivocally protect the freedom of religious and cultural practice, indicating the rights of the communities and individuals to freely practice and manage their religious affairs.

Why is the Waqf Act an infringement on Muslims personal law?

The Constitution so far has strongly supported the notion that once any asset is declared as Waqf, it remains so indefinitely. Despite the obvious safeguards in the Indian Constitution, and several pressing issues on the economic and global front, why has the government chosen to prioritise the amendment of this Act?

The overarching objective appears to be the dilution of Muslim personal laws to weaken the community’s autonomy over shared assets and resources that it has nurtured over centuries for its own upliftment and emancipation.

The government intends to create a structure where it would hold unchecked power over these assets, directly affecting the fundamental notion enshrined in the idea of Waqf. Such a step may compound the already existing disadvantages that the Muslim community currently faces.

The excuses put forth by the Union government to justify the amendments were many, and at times contradictory. The pro-government social media ecosystem was used extensively to amplify these claims.

The first justification was that the Waqf Board has the power to unilaterally declare any property as Waqf, and there were claims that Muslims had taken undue advantage of such clauses from Waqf Act. On the contrary, Waqf records indicate that government as well private entities have illegally encroached Waqf lands for years, paying little to no rent or user fees.

Second, they argued that there was widespread corruption in the management of Waqf properties. The inefficiency of Waqf Boards cannot be denied and discussions about this issue are rife within the internal discourse of the community as well. However, the government, instead of tackling these issues, has further weakened the boards.

Serious problems concerning Waqf Boards’ governance were flagged in the 2006 Sachar Committee Report. It noted that Waqf properties were significantly underutilised, encroachments by government agencies and individuals had led to losses worth thousands of crores and weak governance structures in Waqf Boards had resulted in mismanagement.

One of the contributors of the report, Abusaleh Shariff, wrote that “most Waqf properties have neither been demarcated at site nor mutated in revenue records, despite repeated requests and reminders to relevant revenue authorities. Consequently, many of these valuable properties, often in the heart of a business centre, are either heavily encroached upon or are the subject matter of multiple litigations”.

Also read: Waqf 2025: Beyond Supreme Court Hearing, Doubts About Constitutionality of the Act Still Persist

A 2014 Kundu Committee report reiterated these points. This inefficiency can be partly attributed to gross negligence of the state to appease anti-Muslim sentiments.

A part of the blame also goes to Waqf Board members who fail to combat the transgressions of the state and others on Waqf properties. Additionally, most members have proved themselves incompetent for the job and behave in a corrupt manner.

The government, instead of addressing the issue in the light of SCR recommendations, has further weakened the Waqf Boards by consistently reducing budgetary allocations for their management.

In 2023-24, government spending for Waqf Boards was less than half of the total budgeted amount – Rs 8 crores were spent against the budget amount of Rs 17 crore. It is also questionable that a ruling party that fails to field Muslim candidates in elections, suddenly claims to act in the interest of the poor and disadvantaged Muslims. Such behavioural patterns indicate that the government of the day may not have the best of intentions as far as such amendments are concerned.

Centralisation is not the solution

As of now, the digitisation of Waqf records remains incomplete. There is a strong possibility that, under such severe informational constraints, we may not be making the best decisions.

This concern is particularly urgent as it leaves properties vulnerable to encroachments and disputes. How, then, does the government justify altering Waqf governance before first improving and strengthening existing information systems?

One can only suspect that the intention may be to deal with such disputes through a weaker Waqf law rather than the existing one.

Notwithstanding these commonly raised issues, disproportionate vesting of discretionary power to the central agency is our main concern about these amendments. The Act lays tremendous emphasis on the centralisation of its function and operation which runs contrary to the constitutional ideas of federalism.

Power is being shifted from State Waqf Boards (SWBs) to a strengthened Central Waqf Council (CFC), which was merely an advisory body prior to the new amendment. The CFC is now tasked with overseeing registration and making rules. This posture is consistent with the generic trend of vesting discretionary powers to the Union government or central agencies for subjects that are state responsibilities as per the Constitution.

The present Act, instead of diversifying the governing body and increasing community participation at the SWB level, has created stakes for individuals and groups who cannot be held accountable by the community whose resources they are managing as they are likely to remain far removed from local context.

These amendments, instead of further equipping SWBs with rules that can govern common assets more effectively, has inadvertently raised the chances that Waqf properties may end up as a classic example of tragedy of commons. It is akin to converting a common pool resource of a community into an open access resource. As per Nobel winning political scientist turned economist Elinor Ostrom’s research, while it is possible to govern common pool resources in a sustainable manner, open access resources where user groups are not well defined will cease to exist sooner or later.

There are numerous examples showing that shifting control from local hands to a central authority often leads to trouble. The government’s efforts to centralise the admission procedure in India for higher education through the National Testing Agency so far has yielded many disappointments.

Central control vs local decision making

Under the new Act every Waqf asset must be registered through an online central portal, bypassing local sign-offs. Disputes, previously handled by state tribunals, now head to India’s overburdened courts. It has been claimed that this will bring transparency and fairness.

Critics, however, see it as a disaster.

Economist Ravi Sharma has called it a recipe for “deadweight loss”, a loss for an individual or group that cannot be gained by any member in the society.

The amendments tighten the screws with stricter registration rules and greater government oversight. They centralise control under the Central Waqf Board and overhaul dispute resolution, pulling authority away from local tribunals and pushing cases into the courts.

This shift will disrupt the effective functioning of Waqf properties, creating inefficiencies that will have a ripple effect on services associated with them.

For one, it would increase transaction costs in terms of time, money and effort needed to navigate the new system. It can also cause frustrations due to slow processing of cases owing to the learning curve faced by the CWC and courts. Moreover, it remains uncertain whether the limited organisational capacity of the courts and the CWC will ever be addressed, especially in light of the consistent budget cuts witnessed in recent years.

Take the mandatory registration through a centralised online portal. While it sounds modern, it adds bureaucratic hurdles especially for rural managers who lack reliable internet access and technical know-how.

There are examples of how the JAM (Jan Dhan-Aadhaar-Mobile) model has excluded many bona fide citizens from accessing food and other government schemes.

These added costs don’t stop here. Resources that could go toward maintaining a school or feeding the needy get funnelled instead into managing registrations and fighting legal battles over property disputes. This diverts effort and funds away from the properties’ real purpose, which is serving the community, and locks them into dealing with bureaucracy.

These costs eat into the benefits these assets provide, shrinking their overall value. The market for Waqf-related activities – whether renting land, building on it, or supporting welfare – will start to dry up because no one wants to drain their time and money into a system bogged down by red tape.

By meddling with resource allocation and piling on regulatory layers, they sap efficiency and undercut the community good these assets are meant to deliver. Deadweight loss isn’t just a fancy term here – it’s the real cost of a market thrown out of whack, where the promise of reform might just mean less for everyone.

Ostrom argued that local management of shared resources often outperforms top-down control. In her book, Governing the Commons, she found that communities thrive when they set their own rules, monitor each other and adapt to local needs.

She outlined eight principles, including clear boundaries and community input, that ensure effective resource management which is largely consistent with central notions of Waqf as far as ensuring sustainability of critical assets and resources are concerned.

Regional SWBs, staffed by community leaders, could better manage properties and prevent corruption. Malaysia’s Waqf system, managed by community councils, efficiently builds schools and collects rents. In contrast, India’s centralisation risks inefficiency and distrust, what Ostrom called a “distant bureaucracy trap.”

Historical examples support Ostrom’s views. The Aral Sea disaster, Ethiopia’s 1975 land reform and Zimbabwe’s 2000 land reform – all show the failures of central control and the benefits of local decision-making. Local input could have balanced resource use and prevented these crises.

India’s Waqf reforms risk a similar fate. The central portal and court-based disputes mean delays – potentially years, given the 40 million cases clogging India’s courts – and sidelining of local expertise. Managers might pour funds into legal fees rather than community aid, leaving Waqf less appealing.

The government insists this will stamp out corruption, but Ostrom’s work suggests otherwise. Local overseeing bodies such as SWBs can catch free riders faster and can be better at punishing such transgressors. Given that Waqf disputes are already piled up in state tribunals, the courts will only exacerbate delays.