Initiated in 2014 by the Hon’ble Prime Minister, the Swachh Bharat Mission is considered one of the flagship policies of the central government. It has two components — Swachh Bharat Mission Grameen (SBM-G) and Swachh Bharat Mission Urban (SBM-U). With the ambitious goal of making India “Open Defecation Free” (ODF), The programme initially aimed to address long-standing challenges in hygiene and sanitation practices. Phase II of SBM, launched in 2019, aims at “Open Defecation Free Plus” (ODF Plus) — emphasizing ODF alongside solid and liquid waste management. This phase strives to achieve the broader vision of “Sampoorna Swachhata” or complete cleanliness. The allocation figures for the same stand at approximately USD 17 billion for SBM-G and approximately USD 4 billion for SBM-U.

The Swachh Bharat Mission has been credited with significant progress, particularly in addressing the issue of open defecation. By the conclusion of Phase 1 in 2019, the programme had facilitated the construction of 100 million household toilets, benefiting 500 million people across 6,30,000 villages. According to government estimates from the Drinking Water, Sanitation, Hygiene and Housing Condition survey conducted between July and December 2018, approximately 71.3% of rural households and 96.2% of urban households had access to latrines. Additionally, 61.1% of rural households and 92.0% of urban households had drainage systems for wastewater disposal.

The data illustrates a consistent rise in access to sanitation services among the Indian population since the 2000s, gradually approaching the global benchmark. Notably, India has outpaced countries that had better sanitation metrics in the 2000s. This progress underscores the effectiveness of mission-driven implementation by India’s administrative machinery despite the challenges that continue to exist.

While the numbers are indicative of significant progress, as far as the basics of sanitation are concerned, the full realization of ODF Plus deserves a spotlight on the allied issues of sanitation and public health, such as effective management of faeces waste and inadequate drainage capacity. Thus, our analysis delves into two critical yet under-addressed issues pertaining to sanitation: (a) the prevalence of stagnant water and (b) visible human faeces floating around household premises. These problems, while foundational to the mission’s goals, have not received adequate attention in policy deliberations. Alarmingly, around 20.6% of individuals in India face either or both of these challenges, with rural areas accounting for 22.4% and urban areas for 16.6%. These conditions expose millions to the risks of contamination and diseases such as diarrhoea, cholera and typhoid, underscoring a severe public health concern.

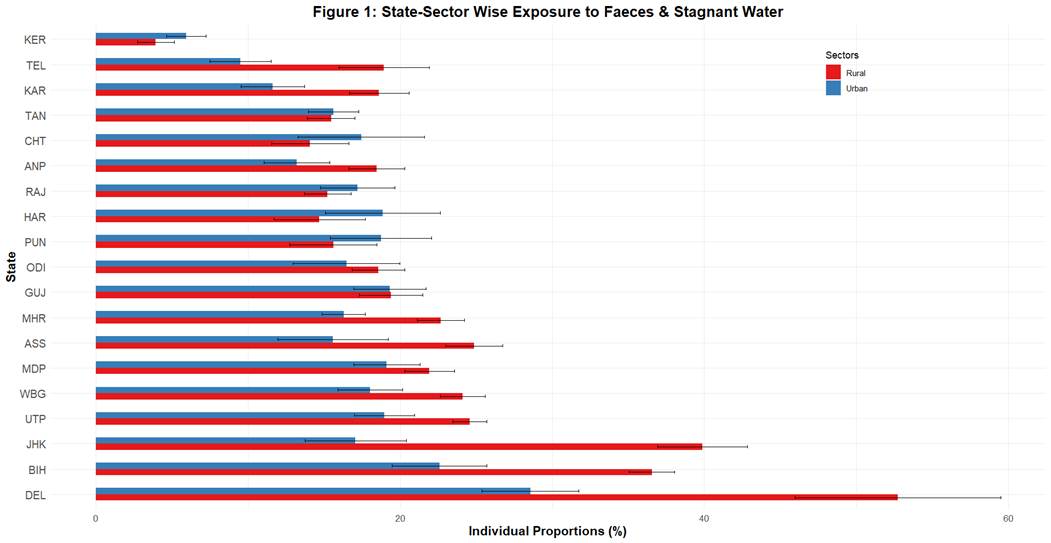

An analysis of key states highlights significant differences in the extent of this problem across the country. Bihar performs the worst, with about 35% of its population facing one or both issues. Jharkhand is close behind, with 34% affected, and even Delhi, the nation’s capital, reports 29% dealing with these challenges. Other states with exposure rates above the national average include Assam (24%), Uttar Pradesh (23%), West Bengal (22%), Madhya Pradesh (21%) and Maharashtra (20%). The high concentration of affected individuals in these densely populated states underscores the urgent need for focused interventions.

In contrast, Kerala— known for its strong human development indicators —performed remarkably well, with only 5% of its population impacted. However, Kerala’s population density of 3,768 persons per square kilometre is significantly lower than states like Bihar (7,802 persons/sq km), Delhi (18,472 persons/sqkm) and Uttar Pradesh (8,171 persons/sq km). This indicates that higher population density contributes to greater exposure to issues such as floating faecal waste and stagnant water.

Like many other policy issues, sanitation too is marked by the rural-urban divide with individuals residing in a rural set-up facing more of this issue. As stated above, close to 22.6% of individuals in rural areas are exposed to either or both the issues compared to 16.6% of individuals in urban areas. An analysis of key states further demonstrates the same. In rural Jharkhand, a staggering 40%faces these sanitation issues, followed by rural Bihar, where the figure stands at 36.5%. The corresponding figures for urban individuals in these states exposed to similar sanitation issues are: 17% and 22.5%, respectively. Even national capital Delhi is not immune —, where 28.5% of urban dwellers encounter these problems. Kerala, however, presents an intriguing case, with more individuals in urban areas (6%) than in rural areas (4%) affected.

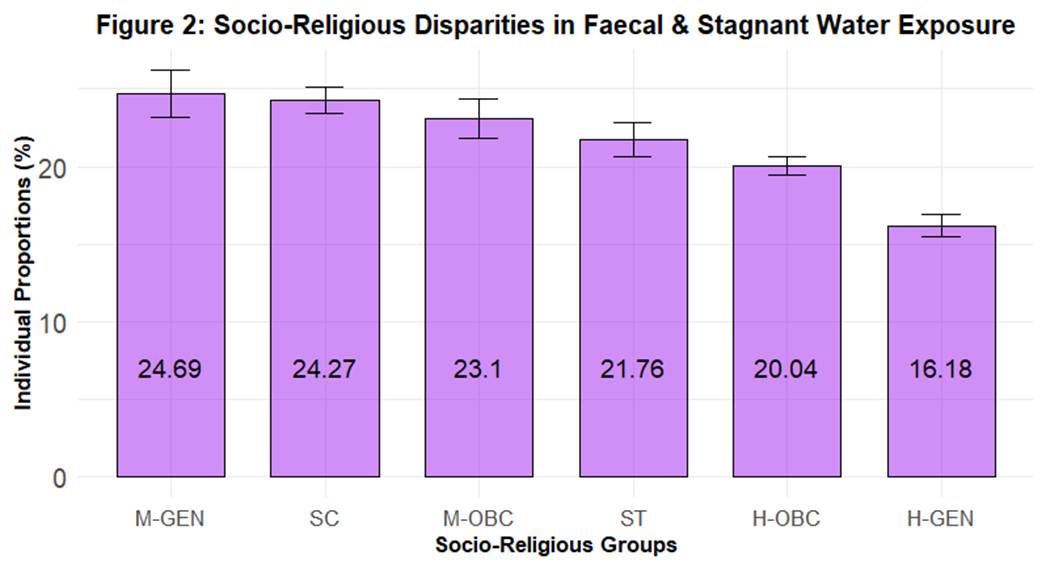

The socio-religious aspect of this analysis reveals another layer of inequality. General Muslims are the most affected group, with 24.6% facing these issues, followed closely by OBC Muslims at 24.2% and Scheduled Castes at 24%. In comparison, the General Hindu population is less affected, with 16% facing these challenges. Scheduled Tribes (21.7%) and Hindu OBCs (20%) also experience significant issues. These figures highlight ongoing inequalities in sanitation access, showing how structural and economic disadvantages often intersect with religion and caste. This underscores the urgent need to address these systemic barriers in sanitation policies.

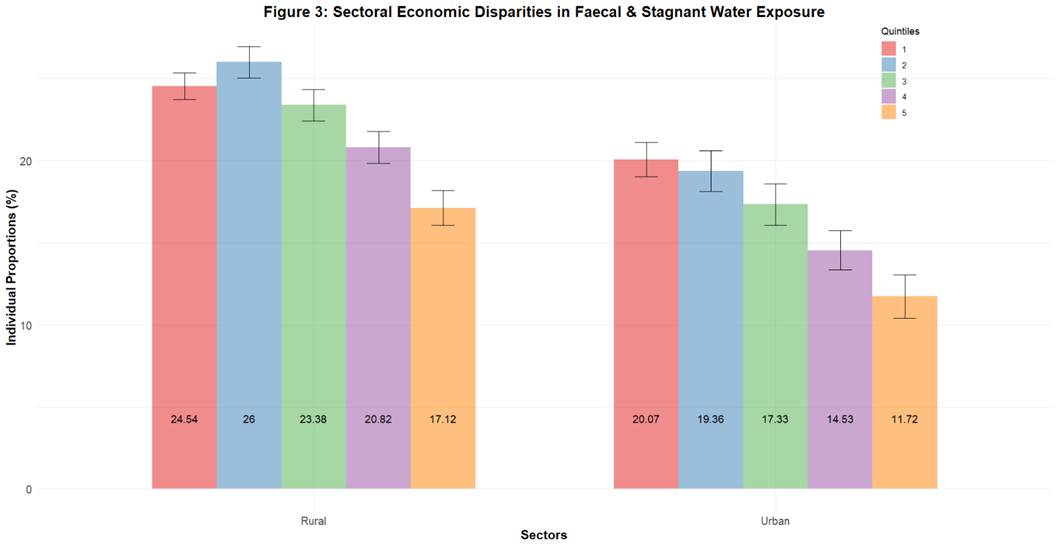

One of the key findings of this study is the narrowing gap between rich and poor in certain states like Bihar, Assam, Karnataka, Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh. In both rural and urban Bihar, about 19.6% of individuals across all economic groups face these issues. Similarly, in Uttar Pradesh, 20% of people across all economic groups are affected in both rural and urban areas. This convergence shows that stagnant water and human waste, as public health hazards, impact individuals across the economic spectrum, highlighting the universal nature of these challenges.

However, at the aggregate level, class differences still play a role in such exposures. For instance, in Delhi, 17% of individuals in the richest economic group face this issue compared to 24% in the poorest group.

Overall, this is an issue that affects people across various groups—whether by class, socio-religious identity or location. It’s worth noting that sanitation challenges like these are not unique to India; they have troubled many now-developed nations during their development stages, such as Britain. What makes India’s situation unique is its high population density, which exacerbates the problem. Historically, sanitation infrastructure in India was neglected, with British investments focused primarily on barrack towns and areas they inhabited. This has left a legacy of historical disregard for sanitation.

The added complexity of caste, tied to notions of purity, further complicates the issue. To drive a broader societal response, it is essential to frame this as a common problem that affects everyone. Our data clearly shows that people from all caste and class groups are impacted, even if the degree of exposure varies.

To conclude, while the Swachh Bharat Mission has made commendable strides in improving sanitation infrastructure, challenges related to stagnant water and human faeces remain pervasive and demand urgent attention. A key factor contributing to the problem is the underutilization of constructed toilets, 26% of the population in rural areas don’t use toilets while the number is around 6% in urban areas, which exacerbates the presence of human faeces in open areas as well as waste water. States with higher proportions of affected individuals, such as Bihar and Jharkhand, require targeted interventions that combine infrastructure development with robust behavioural change campaigns.