Household consumption expenditure — the total amount of money spent by a household on goods and services to meet their needs and wants— is widely used as a measure of welfare.It is considered the best possible proxy for economic status in the context of a developing country as self-reported information on income in surveys are notentirely reliable. The Household Consumption Expenditure Survey (HCES), conducted by the National Sample Survey Office, provides insights into the living conditions of our people. Official poverty estimates are derived fromdata collected duringthis survey. However, after 2011-12, there was a 10-year gap in release ofdata— the 2017-18 data, though prepared, was never officially released.

The data for the latest HCES, 2022-23, has been released.

In common parlance, the average Monthly Per Capita Consumption Expenditure (MPCE) is regarded as a key measure of economic status and living standards. An increasing MPCE reflects an upward trend in consumer spending, indicating an improvement in living standards. It also signifies higher aggregate expenditure, which contributes to economic growth.

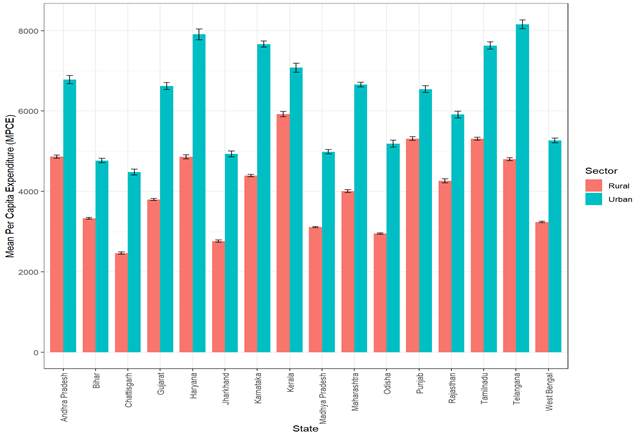

Table 1: Monthly percapita consumption expenditure across states

Source: HCES 2022-23

According to the survey, Telangana accounts for the highest average per capita consumption expenditure in urban areas (₹8,158), while Kerala reports the highest in rural areas (₹5,924). Kerala also exhibits the lowest rural-urban difference in consumption expenditure. In contrast, Chhattisgarh is the worst-performing state in terms of both rural and urban areas. The error bar analysis indicates that the standard error is higher in urban areas compared to rural areas, highlighting the inequality.

Even though the MPCE gives an overall measure of wellbeing, we are particularly interested in the consumption of durable goods because the possession of durable goods by households serves as a more robust indicator of economic wellbeing and standard of living. Fernandez and Krueger (2011) stress the triple role of consumer durables in life-cycle models as an asset, as a long-lived good generating utility flows, and as collateral for borrowing. Analysing household expenditure on durables provides valuable insights into the economic positioning of households, as it reflects their income levels, wealth accumulation, and access to credit, with higher-income households typically owning a wider range of durables (Deaton &Muellbauer, 1980).Investments in durables signal confidence in economic stability and a desire for an improved standard of living.

Durable consumption also has a growth dimension. We may recall Engel’s Law:when household income increases, the percentage of income spent on food (essentials) declines. In a capitalist world, where growth is rooted in profit, consumption must be diversified. Thus, luxury consumption is deeply embedded in the globalized neoliberal growth model (Bhar, 2023). Additionally, as Baxter (1996) argues, consumer durables are widely thought to play a central role in the generation and propagation of business cycles. He reiterates Mankiw’s (1985) view that “Understanding fluctuations in consumer purchases of durables is vital for understanding economic fluctuations generally”. We have not engaged much with this particular aspect, but we mention it here to emphasize the importance of durable consumption patterns in the context of an economy.

Consumer durables includeclothing, footwear, bedding, personal goods, transport equipment, sports goods, medical equipment, cooking & other household appliances, crockery & utensils, furniture & fixtures, goods for recreation, residential building, land and other durables, jewellery & ornaments.

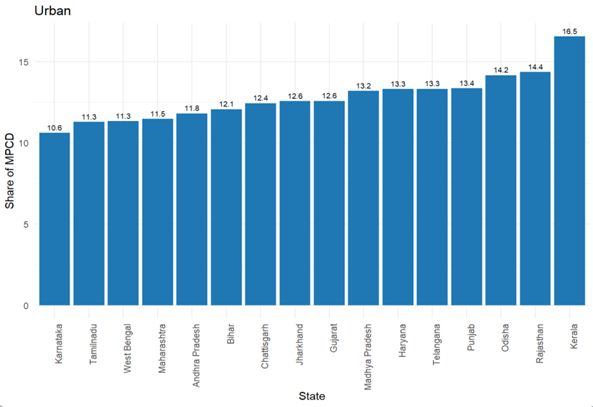

Table 1: Monthly per capita consumption expenditure percentage on durables goods(Urban)

Source: HCES 2022-23

Table 2: Monthly per capita consumption expenditure percentage on durables goods (Rural)

Source: HCES 2022-23

The reference period for recording expenditure on durables goods is 365 days. However, to calculate the overall MPCE, we need to adjust expenditure on every item in the survey to a 30-day scale. Such scaling of expenditure also enables us to draw relative comparisonsinexpenditure on different items with other expenditures by households. For instance, one may be interested in examining the share of expenditure on food items in the total expenditure as Engel’s criteria of living standard envisage.

Since our focus is consumer durable goods, weconcentrate onthe share of monthly per capita consumption expenditure on durable goods (MPCED)formajor states, analyzing rural and urban areas separately. Kerala, which typically exhibits high consumption expenditure, shows that 16.5% of the MPCE is allocated to durable goods in urban area. Whereas, Karnataka has the lowest urban MPCED-to-MPCE ratio, at just 10.6%. When comparing rural and urban differences, Odisha (14.2%) and Punjab (13.4%) show a high urban MPCED-to-MPCE ratio but a low rural ratio,12.2 % and 12.6 % respectively, resulting in a significant rural-urban difference. Conversely, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka exhibit the opposite trend, where the rural MPCED-to-MPCE ratio surpasses the urban ratio, with a considerable difference between the two.

Next, we look at the per capita durable expenditure during thelast 365 days. The annual per capita expenditure on durable goods is ₹ 5,966 in rural areas and ₹ 9,885 in urban areas.

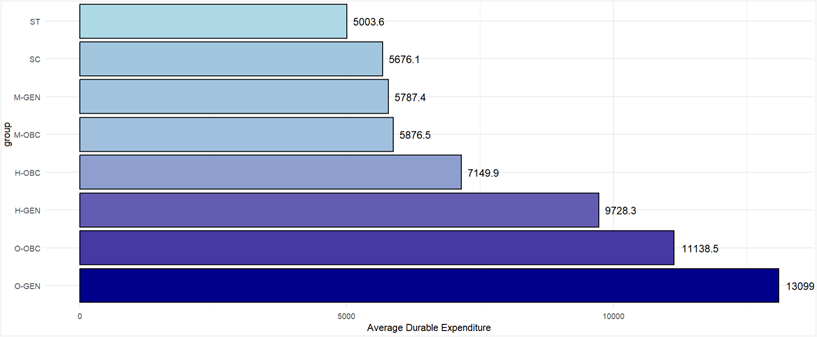

In this analysis, we have attempted an improvised definition of social groups, combining religious groups and social groups as done by Post-Sachar Evaluation Committee. This will giveus a deeper insight since, in India, there are plenty of differences even within a social or religious group. The figure below shows the durable expenditure for the socio-religious groups.

The expenditure is higherfor the General categories of religions other than Muslims. While Christians, Sikhs, Jains and so on, who come under the Others category, have thehighestaverage durable expenditure, SC and ST categories have the lowest expenditure.

Comapred toMuslim OBC and Muslim General categories, Hindu General as well as Hindu OBC are seen to have higher expenditures.

Fig. 1: Average durable expenditure for different groups

Authors’calculation based on HCES 2022-23

These results show that the pattern of social and regional hierarchies within the Indian society is still intact. Even though each group grows in absolute terms, the rate of growth itself is graded based on these social and regional hierarchies. Growth is typically highest for the most advantageous groups while it is lowest for the most disadvantageous groups,resulting in an ever-growing disparity across these groups. India needs to break away from the middle-income trap in order attain the Viksit Bharat status, which requires it to grow by 7 to 8% annually in a sustained manner up to 2047. This will be possible only if we can reverse these social and regional hierarchies in growth rates to level the playing fields for the most disadvantaged group so that they can contribute as effectively.

We are further interested in investigating the state-wise average expenditure ondurable goods in the reference period. Here, we focus on the 18 major states that account for more than 80% of the total Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and population in the country.

Table 1: State-wise average expenditure on durable goods

| State | Average expenditure on durable goods | Standard Error | Relative Standard error |

| Kerala | 12,667.33 | 428.70 | 3.38 |

| Telangana | 10,534.43 | 206.79 | 1.96 |

| Haryana | 9,700.12 | 302.93 | 3.12 |

| TamilNadu | 9,689.86 | 148.84 | 1.54 |

| Uttarakhand | 9,322.85 | 251.23 | 2.69 |

| Punjab | 9,033.75 | 186.65 | 2.07 |

| Rajasthan | 8,331.66 | 165.65 | 1.99 |

| Karnataka | 8,076.97 | 118.95 | 1.47 |

| Andhra Pradesh | 8,023.61 | 163.98 | 2.04 |

| Maharashtra | 7,651.96 | 141.42 | 1.85 |

| Gujarat | 7,609.11 | 191.55 | 2.52 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 5,893.22 | 80.86 | 1.37 |

| Uttar Pradesh | 5,483.94 | 61.22 | 1.12 |

| West Bengal | 5,310.40 | 58.38 | 1.10 |

| Jharkhand | 5,053.74 | 144.75 | 2.86 |

| Odisha | 5,040.20 | 104.12 | 2.07 |

| Bihar | 4,912.83 | 78.54 | 1.60 |

| Chattisgarh | 4,268.20 | 78.46 | 1.84 |

Source: HCES2022-23

Kerala records the highest average expenditure on durable goods at ₹12,667, followed by Telangana (₹10,534) and Haryana (₹9,700). The variation across states is substantial, with Kerala’s expenditure being approximately three times higher than that of Chhattisgarh, which has the lowest expenditure at ₹4,268. Despite this disparity, the relative standard error remains below 5% for all the states, ensuring the reliability of estimates. However, while the estimates are precise, the figures indicate considerable interstate variation in durable goods consumption patterns.

The findings from the consumption expenditure survey generally align with the general indicators of an economy’s health. There are serious issues that need to be addressed, such as the lowest durable consumption among minorities, the urban-rural divide, and regional disparities in consumption, as highlighted by the HCES 2022–23. These issues must be addressed in a timely manner.

Apart from the welfare and growth aspects, durable consumption also has a dimension of structural transformation. In much of the literature on economic development, economic growth is expected to be accompanied by several interrelated processes of structural change (Syrquin, 1988). These processes involve a shift in production, employment, and other economic activities from agricultural/pre-capitalist/rural/informal sectors to industrial/capitalist/urban/formal sectors.

Thus, changes in the consumption of durable goods provide insights into the structural transformation an economy is undergoing. Analysing durable consumption over time offers a perspective on the structural transformation being experienced. Here we have focused solely on the welfare aspect due to the cross-sectional analysis of HCES 2022-23. Further research will explore the growth and structural transformation aspects.

References

Baxter, M. (1996). Are consumer durables important for business cycles? The Review of Economics and Statistics, 78(1), 147–155. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2109854

Bhar, S. (2023). Sustainable consumption and the Global South: A conceptual exposition. Frontiers in Sustainability 4, 965421.

Deaton, A. (1992). Understanding Consumption. Oxford University Press.

Deaton, A., &Muellbauer, J. (1980). Economics and consumer behavior. Cambridge University Press.

Fernández-Villaverde, J., & Krueger, D. (2011). Consumption and saving over the life cycle: How important are consumer durables? Macroeconomic Dynamics, 15, 725–770. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1365100510000180

Kundu, A.& Others (2014). Post Sachar Evaluation Committee.

Mankiw, N. G. (1985). Consumer durables and the real interest rate. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 67(3), 353–362.

Syrquin, M. (1988). Patterns of structural change. In H. B. Chenery & T. N. Srinivasan (Eds.), Handbook of development economics (Vol. 1). Elsevier Science Publishers.