India stands at a crucial juncture in its growth journey, with one of the largest youth populations in the world offering immense potential to shape the nation’s future. Yet, many of them face a harsh reality: the education imparted to them often fails to align with the skills demanded in the job market. With industries reshaped by the Fourth Industrial Revolution, the widening gap between workforce readiness and employer needs poses profound implications for personal as well as national economic growth.

In this dynamic environment, shaped by demographic shifts, technological innovations and globalisation, vocational training holds the key to bridging the divide between education and employment. Unlike traditional education, vocational programmes focus on practical, industry-relevant skills, preparing individuals for specific roles and fostering economic inclusion. As India’s employment landscape continues to evolve, reskilling, skill upgrading and lifelong learning are essential for maintaining employability.Vocational education in India started gaining policy focus with the 11th Five-Year Plan (2007-2012), followed by initiatives like the National Skills Policy (2009) and the National Skill Development Mission (2015).With the cabinet approval for the continuation and restructuring of Skill India Programm—comprising thePradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana 4.0 [PMKVY 4.0], the Pradhan Mantri National Apprenticeship Promotion Scheme [PM-NAPS]and the Jan ShikshanSansthan Scheme[JSSS—understanding employment patterns and focussing on underserved groups through well-designed vocational programmes will be key to addressing the labour market gaps and ensuring equitable, inclusive growth.

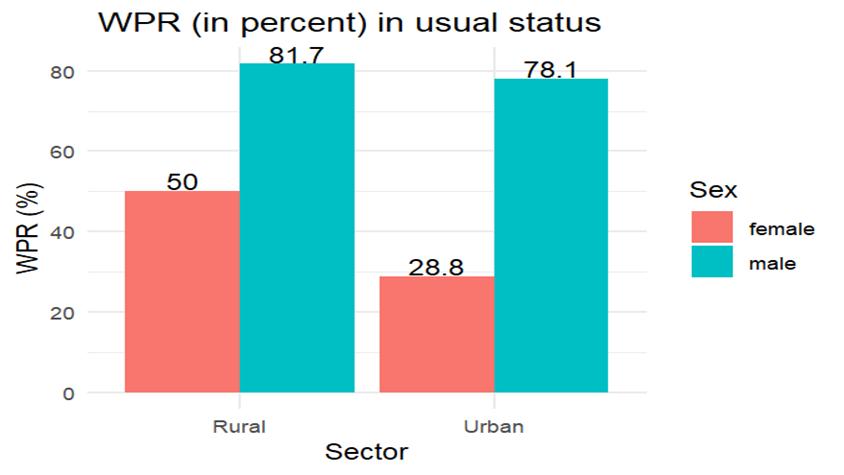

Figure 1: Workforce population ratio in usual status for personsaged 15-59 years(in %)

Source: Author’s calculation based on PLFS 2023-24-unit level data

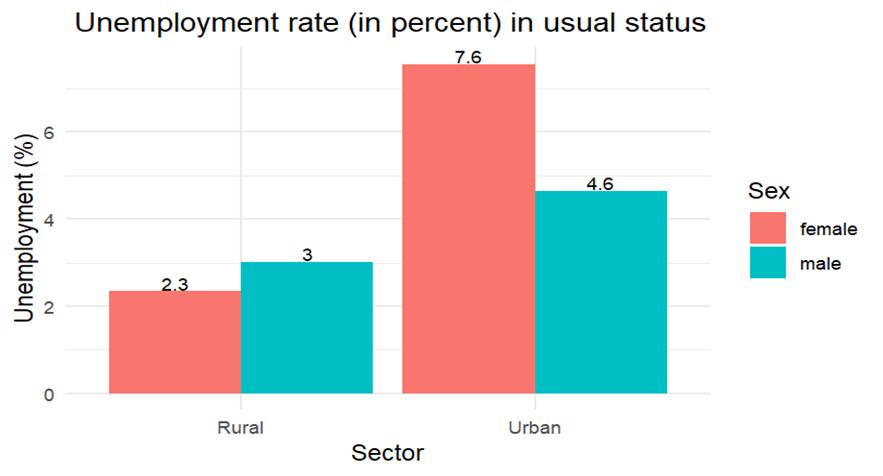

Recent data from the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) 2023-24 reveals encouraging trends in female work force participation rate (FWFPR) across rural and urban areas, signalling progress in gender inclusion. However, the data also underscores a persistent gender gap in workforce participation as India still remains among the countries that have the lowest female participation in the labour market. For instance, the FWFPR in urban areas stands at just 28.8%, significantly lagging behind developed nations. Unemployment figures (Figure 2) further illustrate this disparity. While rural females have a slightly lower unemployment rate (2.13%) compared to rural males (2.70%), urban females face a significantly higher unemployment rate (7.13%) than their male counterparts (4.36%).However, unemployment figures from the PLFS can be misleading, as many women seeking part-time work are classified as being outside the labour force, resulting in an underestimation of their joblessness.

.

According to the World Employment and Social Outlook Trends 2025 released by the International Labour Organization (ILO), South Asia has witnessed a significant rise in labour force participation, driven by increases in female participation, particularly in India. However, much of this growth is driven by women taking on roles as contributing family workers, where their labour often remains unpaid or underpaid, limiting their financial autonomy and perpetuating gender disparities by restricting access to social security and economic empowerment. These statistics point to systemic barriers for women in the Indian labour market, including skill mismatches and lack of adequate job opportunities thatcan tap into a large pool of women willing to work but are available for shorter spans during the day or year.

Figure 2:Unemployment rate in usual status for personsaged 15-59 years (in %)

Source: same as Figure 1

Reports from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) suggest that achieving gender parity in labour participation could boost India’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by 27%. Similarly, Bloomberg projects that equal employment opportunities could expand GDP by 33% by 2050. These figures underscore the economic imperative of reducing gender disparity in the workforce.

Bridging the gaps in workforce participation and unemployment requires interventions, and vocational training could be a game-changer in this regard. By equipping individuals with industry-relevant skills, especially to those without prior skills, these training open doors to employment while driving economic inclusion and productivity. Recognizing the critical role of skilling, the government has launched initiatives such as the PMKVY), which offers short-term skill development programmes, and the Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Grameen Kaushalya Yojana (DDU-GKY), specifically designed to empower the rural youth. Additionally, programmes like the Skill India Mission focus on creating a workforce that meets the demands of evolving industries. Despite these robust efforts, significant challenges remain, particularly for women and marginalized communities. Access to vocational training is far from equitable, with cultural, social and logistical barriers hindering women’s participation. These disparities becomeevident withthe analysis of the vocational training data.

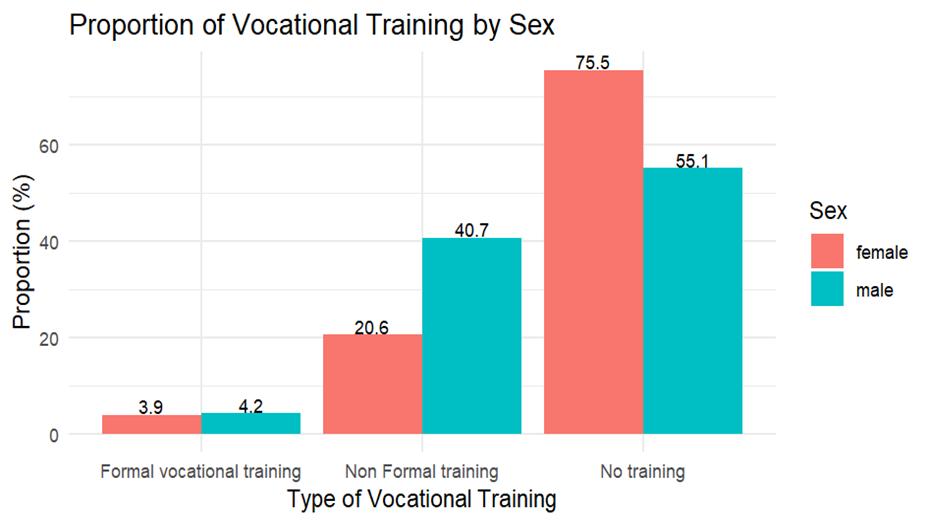

Vocational Training by Gender and Social Group

An analysis of vocational/technical training in Figures 3 and 4 reveals significant gender and social disparities. The proportion of both men and women lacking formal training is notably high, with an alarming percentage of women reporting no training at all. This lack of access to training strongly correlates with women’s low workforce participation rates, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 3: Vocational training for personsaged 15-59 years (in %)

Source: same as Figure 1

*Non-formal training includes categories such as inherent training, learning on the job, self-learning, and others

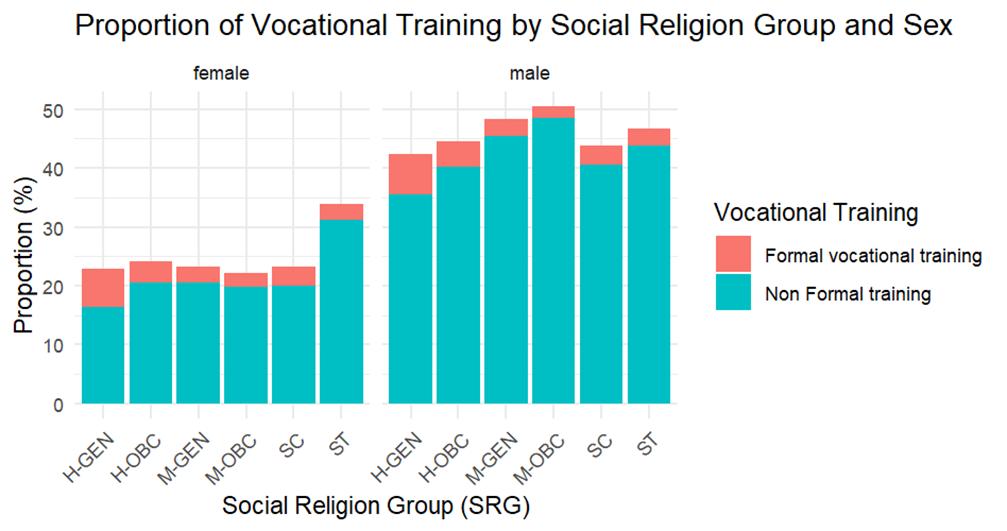

The social group classification adopted here (Figure 4) is an intersection of Social and Religious classification covered by the PLFS. This is based on the classification adopted by Post-Sachar Evaluation Committee headed by Professor Amitabh Kundu. The findings from Figure 4 reveal significant gaps in formal training across gender and socio-religious groups, with Hinduupper caste males (6.84%) and females (6.58%) having the highest participation rates, followed by HinduOBC males (4.26%) and females (3.57%). However, marginalized groups, including Muslims, Scheduled Castes (SC) and Scheduled Tribes (ST), are significantly underrepresented, particularly M-OBC (Muslim – Other Backward Classes), show the lowest participation: 2.12% for males and 2.26% for females. Despite the increased availability of vocational training programmes since the launch of the Skill India Programme , a large portion of the workforce remains without formal training, with significant disparities across socio-religious groups, particularly among marginalized communities.

Figure 4: Vocational training for personsaged 15-59 years in different Social Religion Group(in %)

Source: same as Figure1

(Residual groups, i.e., other religions falling under General and OBC categorieshave been omitted since their weighted percentage was only 1.4 and 0.8, respectively.)

Gender disparities are pervasive across all groups, with women consistently having less access to formal training than men. This gap is particularly evident among marginalized communities, where economic and social barriers further restrict opportunities. In response to these limitations, many women turn to informal pathways like self-learning and on-the-job training. For instance, 31.19% of ST females report relying on self-acquired skills, a trend also seen among others. Across all groups, men participate in non-formal training more than women. Muslim males have a higher rate of non-formal training such as 48.41% for OBC Muslims and 45.46% for General Muslims. In the case of Scheduled Tribes (ST), 43.82% of males receive non-formal training, compared to only 31.19% of females. The table has been provided in the appendix.

The irony is that a large chunk of individuals isacquiring vocational skills in a non-formal manner but theskills remain unrecognised as they are never certified. Designing a robust mechanism tocertify skills that are informally acquired will greatly pave the way towards labour market mobility of such individuals. Unfortunately, the government offers a large battery of training programmes but so far there is no mechanism to recognise and certify skills that are acquired through informal means.

This write-upunderscores the critical need for policymakers to prioritize inclusive strategies to eliminate disparities between social and gender groups. Expanding institutional training access—particularly for women and marginalized communities—while ensuring that training translates into full-time employment is essential. Strengthening quality standards, a robust system of recognising and certifying informally acquired vocational training, and fostering industry linkages will create a more equitable and skilled workforce. Addressing these systemic challenges is vital to ensuring that vocational and technical programmes serve as a catalyst for social and economic development.

Conclusion

Vocational/technical training challenges deep-rooted gender norms and empowers women and marginalized groups to enter previously inaccessible fields such as technology, engineering and leadership. Most importantly, it ensures their integration into the formal workforce. As a key driver of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—particularly SDG 5 (Gender Equality), SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities)—it has the potential to create inclusive and sustainable employment opportunities. Initiatives like the PMKVY and DDU-GKY have made strides in addressing skilling gaps, while the PM-DAKSH Yojana has focused on upskilling and entrepreneurial development for socially, educationally and economically marginalized communities. However, despite ambitious targets and substantial investments, persistent challenges continue to hinder equitable access and effectiveness.

A quality-driven approach is essential to ensure that vocational training delivers tangible outcomes instead of merely increasing number of formally trained individuals who cannot withstand the demands of skill while they are in jobs. Policiesmust be inclusive of people who acquired skills through informal means using transparent and accountable certification process. Existing programmes cater to internships or on-the-job training but only in the formal sector. Given the huge size of India’s informal sector, it is important to tap into the skills acquired in the informal sector and formalise them through certification process.

Women and marginalized communities, who already face structural barriers, require training programmes that address their unique socio-economic constraints. Aligning vocational education with industry demands, strengthening apprenticeship programmes, and expanding employment opportunities for trained individuals will enhance workforce integration and maximize the impact of skill development initiatives.

Bridging existing disparities demands a shift from certification-focused training to skills-based, industry-relevant and inclusive learning models. Expanding access to non-traditional fields, introducing gender-sensitive learning platforms, and fostering collaboration between training providers and industry stakeholders will create more equitable pathways to employment. With targeted policies and continued investment in skilling ecosystems, India can unlock the full potential of its workforce. A systematic overhaul of vocational programmes is crucial to ensuring long-term sustainable employment opportunities, reducing economic vulnerabilities, and empowering individuals and communities.

Appendix

Table 1: Vocational training for females and malesaged 15-59 years in different socio-religiousgroups (in %)

| Female | Male | |||||

| Socio- Religious Group | Formal Vocational Training | Non-formal Training | No Training | Formal Vocational Training | Non-formal Training | No Training |

| H-GEN | 6.58 | 16.38 | 77.04 | 6.84 | 35.52 | 57.64 |

| H-OBC | 3.57 | 20.49 | 75.94 | 4.26 | 40.23 | 55.51 |

| M-GEN | 2.77 | 20.52 | 76.71 | 2.78 | 45.46 | 51.76 |

| M-OBC | 2.26 | 19.89 | 77.85 | 2.12 | 48.41 | 49.46 |

| SC | 3.29 | 20.01 | 76.70 | 3.31 | 40.54 | 56.15 |

| ST | 2.72 | 31.19 | 66.09 | 2.94 | 43.82 | 53.24 |